Consensus models are a primary component of distributed blockchain systems and definitely one of the most important to their functionality. They are the backbone for users to be able to interact with each other in a trustless manner, and their correct implementation into cryptocurrency platforms has created a novel variety of networks with extraordinary potential.

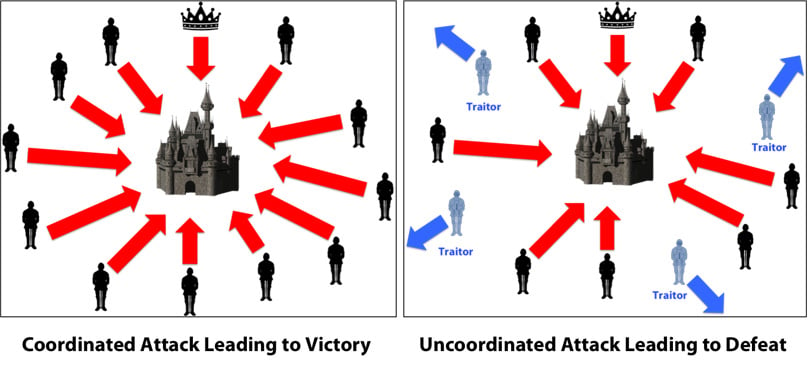

In the context of distributed systems, Byzantine Fault Tolerance is the ability of a distributed computer network to function as desired and correctly reach a sufficient consensus despite malicious components (nodes) of the system failing or propagating incorrect information to other peers.

The objective is to defend against catastrophic system failures by mitigating the influence these malicious nodes have on the correct function of the network and the right consensus that is reached by the honest nodes in the system.

Derived from the Byzantine Generals’ Problem, this dilemma has been extensively researched and optimized with a diverse set of solutions in practice and actively being developed.

Byzantine Generals’ Problem, Image by Debraj Ghosh

Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (pBFT) is one of these optimizations and was introduced by Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov in an academic paper in 1999 titled “Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance”.

It aims to improve upon original BFT consensus mechanisms and has been implemented and enhanced in several modern distributed computer systems, including some popular blockchain platforms.

Quick Verdict: Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance is an algorithm that allows distributed systems like blockchains to securely reach consensus despite malicious nodes through extensive node communication to verify messages and system state.

Key Facts

| Key Facts | Description |

|---|---|

| Consensus Models | Critical for the functionality of distributed blockchain systems, enabling trustless interactions between users. |

| Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) | A network’s capacity to reach consensus despite having nodes that may fail or act maliciously. |

| Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (pBFT) | An optimization of BFT, introduced by Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov in 1999, implemented in modern systems to improve performance and security. |

| pBFT Algorithm | Works under the assumption that less than 1/3 of the nodes are malicious. It provides both liveness and safety and ensures linearizability, meaning that client requests yield correct responses. |

| pBFT Node Structure | Consists of one primary (leader) node and multiple backup nodes, where the leader is changed in a round robin manner. |

| pBFT Communication and Phases | Heavy inter-node communication with 4 phases: a client’s request to the leader, multicast to backups, execution and reply, and the client awaits f+1 matching replies. |

| Transaction Finality and Energy Efficiency | pBFT provides immediate transaction finality and is less energy-intensive compared to Proof-of-Work models, thereby reducing the network’s energy consumption. |

| Limitations | Best suited for small consensus groups due to heavy communication overhead. The algorithm’s scalability and high-throughput capability diminish as the network size increases. |

| Message Authentication | Utilizes digital signatures and multisignatures rather than MACs for efficient authentication in large groups, improving over the original pBFT’s limitations. |

| Susceptibility to Attacks | Vulnerable to Sybil attacks, although mitigated by larger network sizes. The challenge remains to maintain security while overcoming communication limits for scalability. |

| Modern Implementations | Blockchain platforms like Zilliqa use optimized pBFT for high throughput, combined with PoW for additional security in their consensus model. Hyperledger Fabric uses a permissioned pBFT variant, benefiting from smaller, known consensus groups for high transaction throughput. |

| Importance for Cryptocurrencies | Advanced BFT mechanisms are crucial for the integrity and trustless nature of large-scale public blockchain systems, with pBFT being a foundational technology for many current cryptocurrencies. |

An Overview of Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance

The pBFT model primarily focuses on providing a practical Byzantine state machine replication that tolerates Byzantine faults (malicious nodes) through an assumption that there are independent node failures and manipulated messages propagated by specific, independent nodes.

The algorithm is designed to work in asynchronous systems and is optimized to be high-performance with an impressive overhead runtime and only a slight increase in latency.

- Essentially, all of the nodes in the pBFT model are ordered in a sequence with one node being the primary node (leader) and the others referred to as the backup nodes.

- All of the nodes within the system communicate with each other and the goal is for all of the honest nodes to come to an agreement of the state of the system through a majority.

- Nodes communicate with each other heavily, and not only have to prove that messages came from a specific peer node, but also need to verify that the message was not modified during transmission.

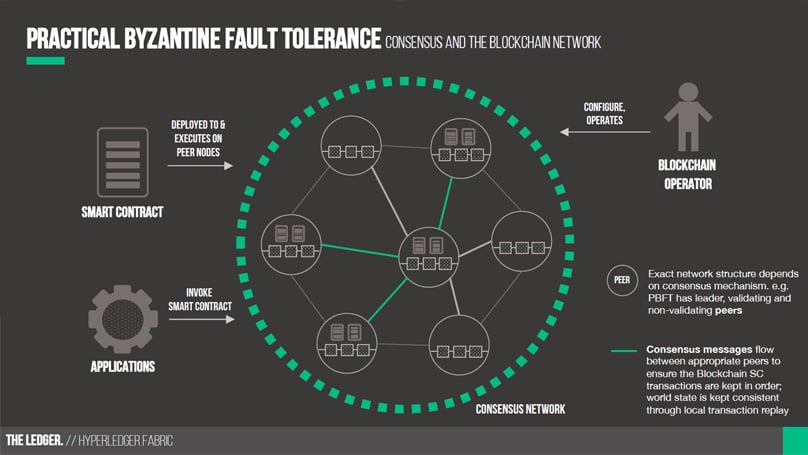

Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance, Image by Altoros

For the pBFT model to work, the assumption is that the amount of malicious nodes in the network cannot simultaneously equal or exceed ⅓ of the overall nodes in the system in a given window of vulnerability.

The more nodes in the system, then the more mathematically unlikely it is for a number approaching ⅓ of the overall nodes to be malicious. The algorithm effectively provides both liveness and safety as long as at most (n-1) / ⅓), where n represents total nodes, are malicious or faulty at the same time.

The subsequent result is that eventually, the replies received by clients from their requests are correct due to linearizability.

Each round of pBFT consensus (called views) comes down to 4 phases. This model follows more of a “Commander and Lieutenant” format than a pure Byzantine Generals’ Problem, where all generals are equal, due to the presence of a leader node. The phases are below.

- A client sends a request to the leader node to invoke a service operation.

- The leader node multicasts the request to the backup nodes.

- The nodes execute the request and then send a reply to the client.

- The client awaits f + 1 (f represents the maximum number of nodes that may be faulty) replies from different nodes with the same result. This result is the result of the operation.

The requirements for the nodes are that they are deterministic and start in the same state. The final result is that all honest nodes come to an agreement on the order of the record and they either accept it or reject it.

The leader node is changed in a round robin type format during every view and can even be replaced with a protocol called view change if a specific amount of time has passed without the leader node multicasting the request.

A supermajority of honest nodes can also decide whether a leader is faulty and remove them with the next leader in line as the replacement.

Advantages and Concerns With the pBFT Model

The pBFT consensus model was designed for practical applications and its specific shortcomings are mentioned in the original academic paper along with some key optimizations to implement the algorithm into real-world systems.

On the contrary, the pBFT model provides some significant advantages over other consensus models.

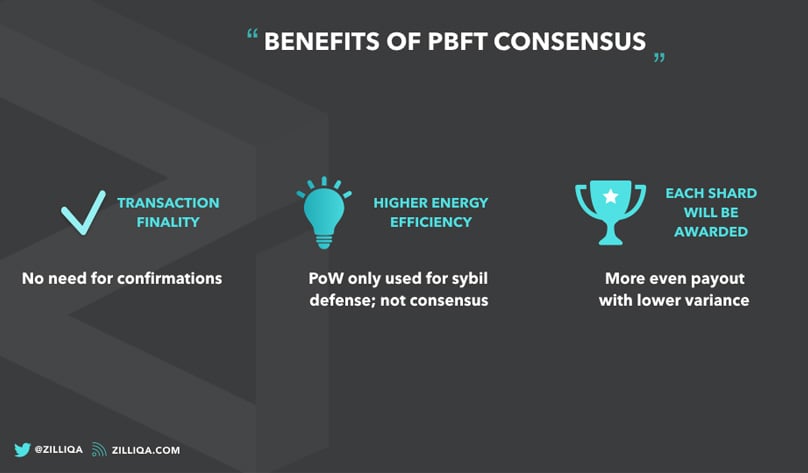

Benefits of pBFT, Image by Zilliqa

One of the primary advantages of the pBFT model is its ability to provide transaction finality without the need for confirmations like in Proof-of-Work models such as the one Bitcoin employs.

If a proposed block is agreed upon by the nodes in a pBFT system, then that block is final. This is enabled by the fact that all honest nodes are agreeing on the state of the system at that specific time as a result of their communication with each other.

Another important advantage of the pBFT model compared to PoW systems is its significant reduction in energy usage.

In a Proof-of-Work model such as in Bitcoin, a PoW round is required for every block. This has led to the electrical consumption of the Bitcoin network by miners rivaling small countries on a yearly basis.

With pBFT not being computationally intensive, a substantial reduction in electrical energy is inevitable as miners are not solving a PoW computationally intensive hashing algorithm every block.

Despite its clearcut and promising advantages, there are some key limitations to the pBFT consensus mechanism. Specifically, the model only works well in its classical form with small consensus group sizes due to the cumbersome amount of communication that is required between the nodes.

The paper mentions using digital signatures and MACs (Method Authentication Codes) as the format for authenticating messages, however using MACs is extremely inefficient with the amount of communication needed between the nodes in large consensus groups such as cryptocurrency networks, and with MACs, there is an inherent inability to prove the authenticity of messages to a third party.

Although digital signatures and multisigs provide a vast improvement over MACs, overcoming the communication limitation of the pBFT model while simultaneously maintaining security is the most important development needed for any system looking to implement it efficiently.

The pBFT model is also susceptible to sybil attacks where a single party can create or manipulate a large number of identities (nodes in the network), thus compromising the network.

This is mitigated against with larger network sizes, but scalability and the high-throughput ability of the pBFT model is reduced with larger sizes and thus needs to be optimized or used in combination with another consensus mechanism.

Platforms Implementing Optimized Versions of pBFT Today

Today, there are a handful of blockchain platforms that use optimized or hybrid versions of the pBFT algorithm as their consensus model or at least part of it, in combination with another consensus mechanism.

Zilliqa

Zilliqa employs a highly optimized version of classical pBFT in combination with a PoW consensus round every ~100 blocks. They use multisignatures to reduce the communication overhead of classical pBFT and in their own testing environments, they have reached a TPS of a few thousand with hopes to scale to even moreas more nodes are added.

This is also a direct result of their implementation of pBFT within their sharding architecture so that pBFT consensus groups remain smaller within specific shards, thus retaining the high-throughput nature of the mechanism while limiting consensus group size.

Hyperledger

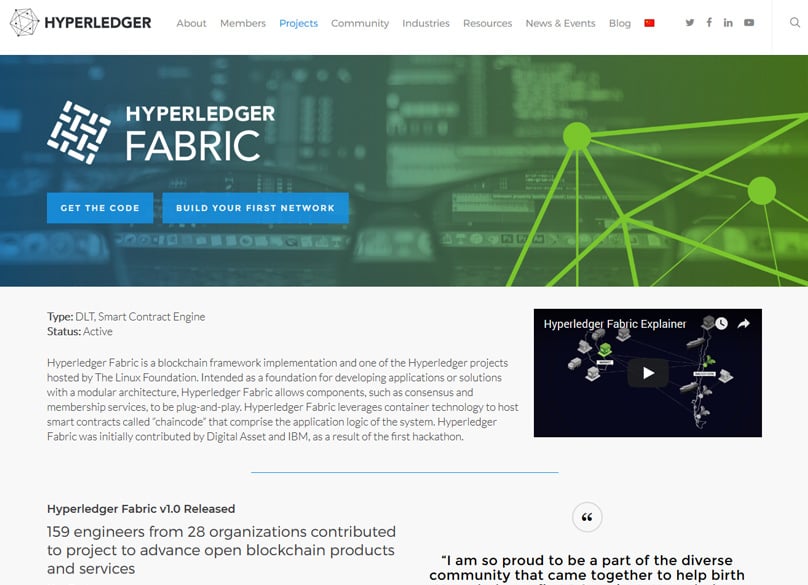

Hyperledger Fabric is an open-source collaborative environment for blockchain projects and technologies that is hosted by the Linux Foundation and uses a permissioned version of the pBFT algorithm for its platform.

Since permissioned chains use small consensus groups and do not need to achieve the decentralization of open and public blockchains such as Ethereum, pBFT is an effective consensus protocol for providing high-throughput transactions without needing to worry about optimizing the platform to scale to large consensus groups.

Additionally, permissioned blockchains are private and by invite with known identities, so trust between the parties already exists, mitigating the inherent need for a trustless environment since it is assumed less than ⅓ of the known parties would intentionally compromise the system.

Conclusion

Byzantine Fault Tolerance is a well studied concept in distributed systems and its integration through the Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance algorithm into real world systems and platforms, whether through an optimized version or hybrid form, remains a key infrastructure component of cryptocurrencies today.

As platforms continue to develop and innovate in the field of consensus models for large-scale public blockchain systems, providing advanced Byzantine Fault Tolerance mechanisms will be crucial to maintaining various systems’ integrity and their trustless nature.

9 Comments

… as long as at most `(n-⅓)` are malicious or faulty at the same time.

n minus ⅓ ?????

(n-1)/3

Shah has it right – should be (n-1)/3… the text may have been improperly formatted after copying from this kind of format:

n-1

___

3

Yes, I noticed the same thing. I am not a smart guy, so I read the thing ten times. 😀 It should say, where (n – 1/3) of the nodes are NOT malicious.

>> client awaits f + 1 (f represents the maximum number of nodes that may be faulty) replies from different nodes with the same result.

Is it 3f+1 (to satisfy the 2/3 rd rule)?

No, they only need to wait for f + 1.

If there are maximum f liars, and you hear back with more than f replies, at least one reply will be honest. If you get f+1 replies which are all the same, and you know that at least one was honest, then you know they’re all honest.

(3f+1) describes the size of the total population in terms of f, the number of faulty nodes. The honest population must be more than double the faulty population for this to work… so if there are f faulty, the honest must number (2f + 1), and the total population is (3f + 1).

” If you get f+1 replies which are all the same, and you know that at least one was honest, then you know they’re all honest.”

How is that true? If there are 100 people in a group, and f is 33, then if I get 33 + 1 = 34 replies that are all the same, why is it impossible that the 35th reply couldn’t be a liar?

It seems logical that I would have to receive 2f+1 replies before I can know they are ALL honest, because that would be the inversion of f.

Please explain.

Great article by the way!

It’s not about a 35th reply… you’re throwing yourself off by thinking about the next reply. Back up for a moment:

If f = 33, then AT MOST 33 people in the whole group of 100 are liars.

When you receive 34 replies, then you have AT LEAST one honest person in your group of replies, even if (by chance) the other 33 are all liars.

IF your 34 replies are ALL the same, and AT LEAST one of them is honest, then all of those 34 replies must be giving the honest reply: they all match each other, and you know one of them is honest. You now know, for sure, what the honest reply is.

It makes no difference what a “next” reply would say – you already know what the honest answer must be. It isn’t impossible that a 35th answer comes in, and it may be lying… but if it is lying, you’d know, because you already know the honest answer from having already received 34 matching answers!

Of course, all of the above is only true so long as there aren’t actually more dishonest actors than f… and if your initial group of 34 replies are NOT all the same, then you know some of them are lying, but at least you’re aware that someone is lying and that you don’t yet know the truth.

How PBFT is achieved in Hyperledger fabric ?